What happened

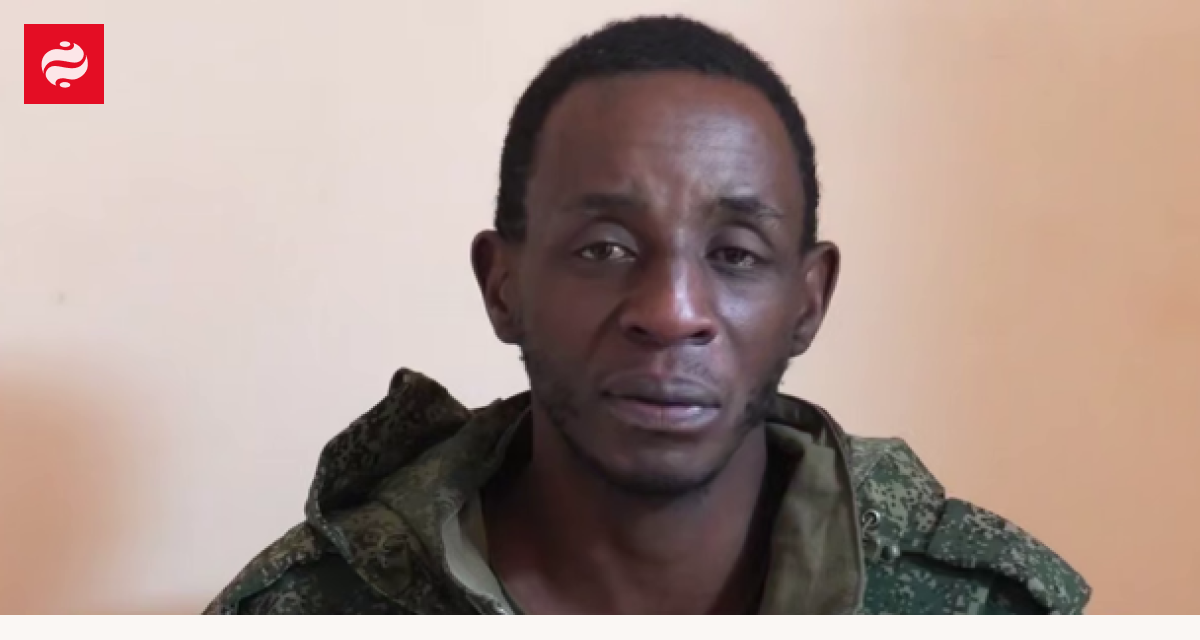

At the end of 2025 a man approached one of the checkpoints near Lyman who identified himself as a native of Uganda. A video recording of his testimony was published by the 63rd Separate Mechanized Brigade, part of the Third Army Corps. According to the captive, he was lured to Russia with promises of work and then forced to sign a military contract under threat of a weapon.

With the start of autumn, pilots and infantry of the 63rd Brigade managed to neutralize dark-skinned Russian mercenaries who, armed, were moving toward our positions. They had no documents on them, so it was impossible to identify the arrivals.

— 63rd Separate Mechanized Brigade

Richard's story

The man called himself Richard. According to him, he took out a large loan for plane tickets and came to Russia in search of work in a supermarket. Instead, he and several compatriots were taken to Balashikha, where they were given a choice: sign a contract or die from a shot to the head. At least one person in the group, Richard said, was brought before a soldier with a service automatic weapon that was placed against his head to force him to sign the documents.

We drove in, and they told us: sorry, guys, but now you're in the Russian army. We said no, no — we didn't come for this — but they replied that the gates were locked and there was no way out.

— Richard, native of Uganda (per the recording of the 63rd Brigade)

How foreigners are recruited

Not an isolated case, but a system. Bloomberg has already reported that the recruitment of foreigners in various regions and units of Russia takes place through online platforms — including Discord and gaming communities. The combination of economic vulnerability, promises of earnings, and coercion makes this practice both attractive to recruiters and catastrophic for those who are recruited.

What this means for the front and for the world

First, Richard's case is an indicator of personnel shortages and a reputational crisis in the Russian forces: when resources are directed toward recruiting foreigners, it signals problems within the Kremlin's mobilization logistics.

Second, this is not only about military strength but about human-trafficking networks and information channels that enable such recruitment. This should become a focus not only for Ukrainian intelligence but also for international human-rights organizations and partners who document violations of human dignity.

Third, for Ukraine this is a source of intelligence: the interrogated and published testimonies provide insight into routes, camps, and methods of coercion, which can help disrupt these networks and improve security at the front.

Conclusion

The story of one captive from Uganda is more than the tragedy of an individual. It demonstrates how the combination of economic blackmail and military coercion works to weaken neighboring states while also exposing vulnerabilities within Russia itself. The next question is for the international community and Ukrainian authorities: will they be able to turn these testimonies into systemic measures against the recruitment and human-trafficking networks that fuel the war?